Victoria Middleton

Writer / Historical Researcher

Biography

A resident of Barmedman, Victoria is a Historical Researcher, Government Scribe and the Editor & Designer of The Mallee Stump,

a triannual journal of

Wyalong District Family History Group Inc.Victoria has traced her ancestors to 978 A.D.

when her 35th great-grandfather,

Fulbert Pelletier de Falaise of Normandie, France, was born—

the maternal grandfather of William the Conqueror.With a background in Fine Arts, Design, Marketing and Content Writing, Victoria is a prolific researcher of local and Australian history.Victoria is the author of 2 published fiction novels,

Gem: The Season of Prophecy

The Fractured Race.

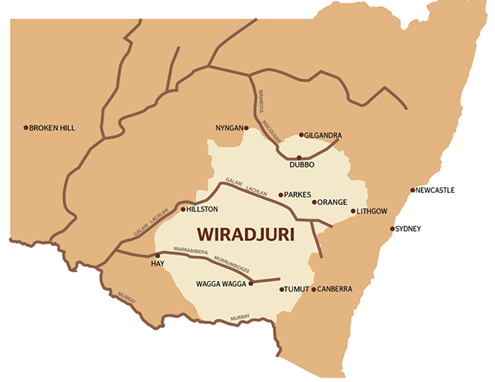

The Wiradjuri and the White Man (1788-1900)

by Victoria Middleton

The 'River People', as the Wiradjuri were called by the first white settlers, lived on the wheat belt plains of the Central West, West Wyalong and Barmedman, with the Lachlan River (the Kalare) intersecting their land.

In 1788, it is estimated that of the 3000 Aborigines living in Wiradjuri lands, clans of at least 430 people lived in the Barmedman area.The clans were divided into small groups for the benefit of socialising and food-gathering. Each group held at least one extended family, such as an old man and his wives, his sons and their families.These families would move to a new campsite about six times a year, within a forty kilometre radius.

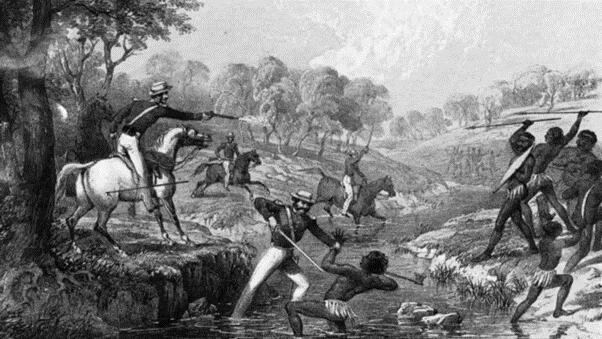

There were Aborigines on the Lachlan at the time of the first white explorers, and the clans took the European names for the towns. These regions where they lived dictate the borders of Wiradjuri country.In 1841, the pastoralists south of Barmedman won a bitter campaign against the Wiradjuri with atrocities decimating a great number of family groups, sometimes leaving only the women and children to fend for themselves. Disease would take them when they ventured near the towns and many clans were wiped out this way.

In 1870, after years of confrontation with the Wiradjuri from the law, missionaries and white do-gooders, the Church and State retreated for four decades, and the missions collapsed. 1840 to 1880 was the time of the great expansion of settlers and miners, and the Wiradjuri struck whatever bargains they could to maintain peace.Some Barmedman settlers would parley with the Wiradjuri to provide work for the women in the homestead or paddocks and use the men as trackers or sheep washers.

No sooner had the Wiradjuri adjusted to the new reality of the pastoral stations when, in 1874, the gold-diggers came to Barmedman. The Chinese labourers disrupted the tenuous relations, but the claims and holdings worked on by the hundreds who came to the area from that date, pushed the Wiradjuri away from town and not even the pastoral stations could give them casual work.There was not one Aboriginal name recorded on the shearing records after this time. After twenty years of grazing, the farms of the Barmedman District ensured that no Wiradjuri person could live independently of the whites and many Aborigines were close to starvation.

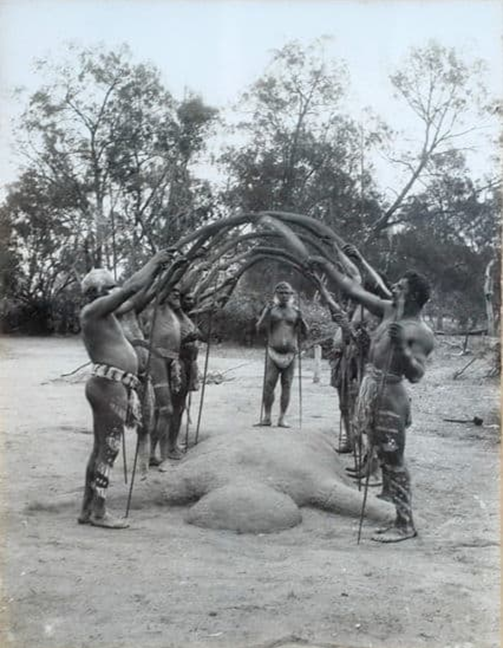

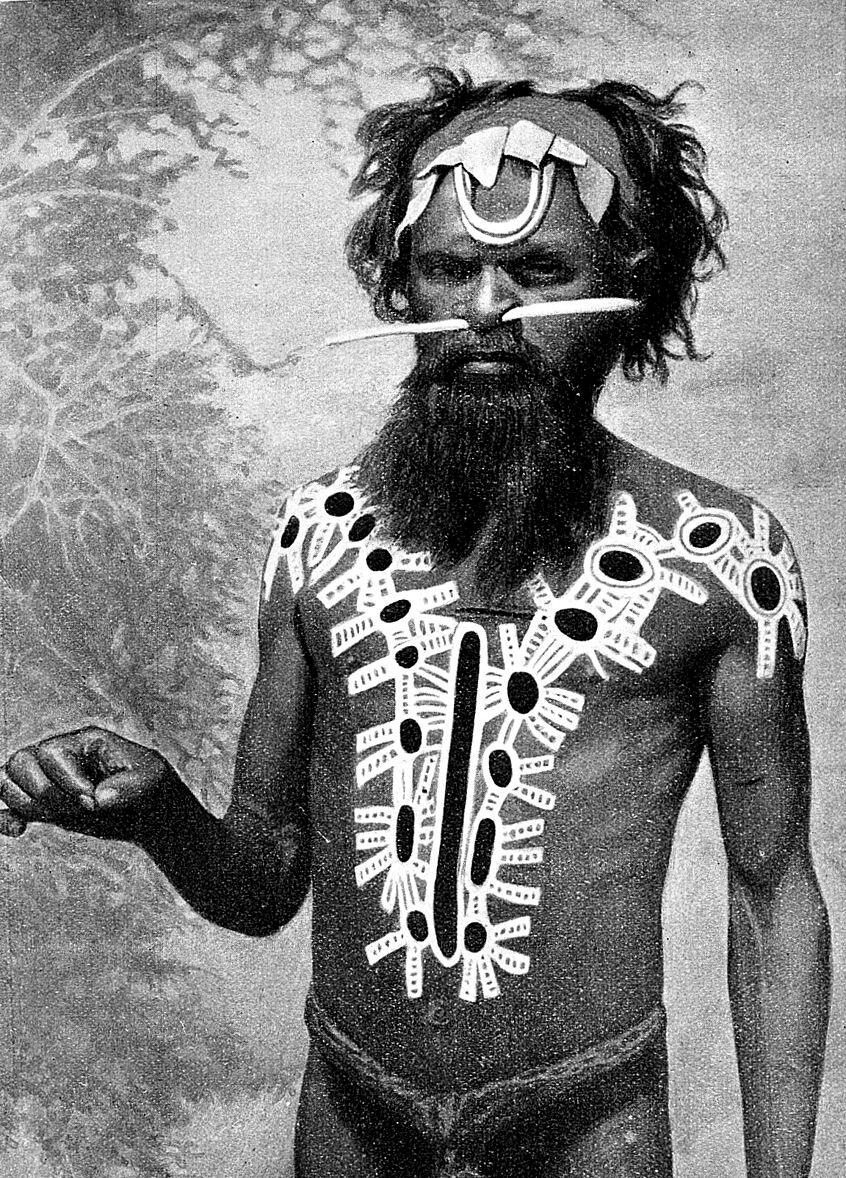

By the 1880s, the larger rituals had gone and only the ceremonial cultural practices were maintained by the Wiradjuri, and these were in decline.

After decades of doing nothing, the State granted land to missionaries seeking to help the indigenous peoples, and then ran them out of business. It established the Aboriginal Protection Board and created hundreds of Aboriginal reserves, eventually losing control of them before passing the Aborigines Protection Act, and attempted to turn the black people to white in one generation.For the few Aborigines camped on the Bland River to Back Creek, conditions were more than tenuous with the white settlers, who a missionary named Gribble quoted one wife as saying, “If she had her way, all the 'half-caste children would be thrown into the river."By 1880, most of the Aboriginal groups had moved to the State reserves, like Maloga Mission on the Murray, and Reverend Gribble’s Warangesda near Parkes.

In 1883, the Aborigines Protection Board was established and it was devoted to the destruction of Aboriginal society in NSW. This gave the Board wide-ranging control over the lives of the Wiradjuri and all Aboriginal people, including the power to remove children from families because their parents were Aboriginals, as was written on many of the files, and the power to dictate where Aboriginal people lived to ensure protection from violent colonialists and provide education in the face of European opposition.The Board controlled their freedom of movement and personal finances. In particular, Aboriginal children could be removed from their homes and families and taken into care to be raised like white children, thus starting the Stolen Generations.From the beginning, the whites have interfered in every aspect of Aboriginal life making it impossible to separate what is purely Aboriginal. They were the teachers, Health Inspectors, Town Clerk, the station manager and his wife, and the Police Sergeant. During the nineteenth century, the Wiradjuri were delivered, christened, married and buried by whites.

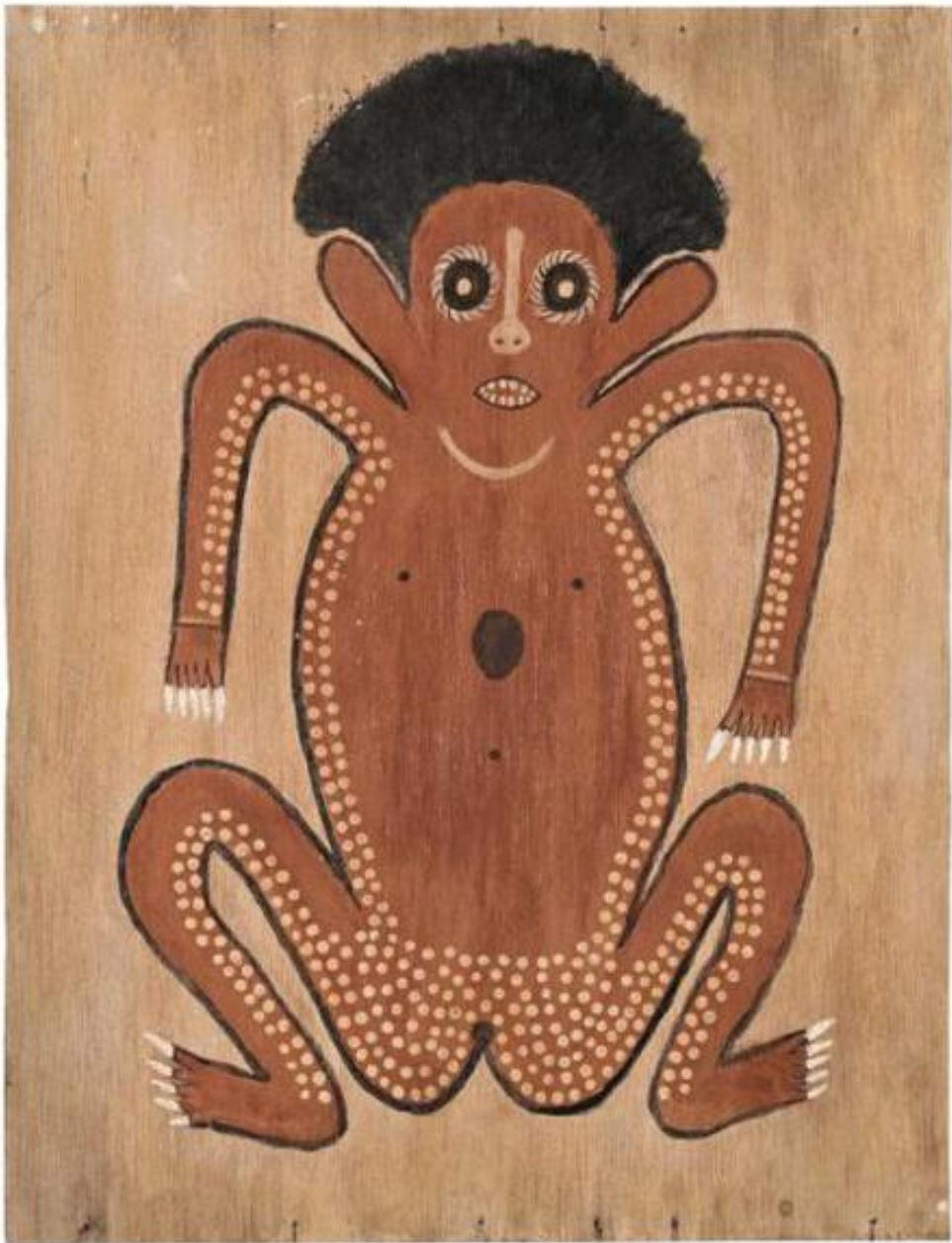

The Gugaa (goanna) is the Wiradjuri Totem

Sources:

>Read, Peter, 1888, A Hundred Years of War: the Waradjuri People and State

>First Nations of the SouthEast Region, Austlit.edu.au, page/15517944

>https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-17/curious-central-west-how-the-wiradjuri-survived-first-contact/10128822

>https://www.envirostories.com.au/wp-content/uploads/pdf/2016044DarlingtonPointWEB.pdf

>https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334272384BAIAMIANDTHEEMUCHASEANASTRONOMICALINTERPRETATIONOFAWIRADJURIDREAMINGASSOCIATEDWITHTHEBURBUNGBAIAMI-BUDHINAWANYANHAMANHAGIBBIRGIRRBAANGWINHANGA-DURIN-YAWIRADJURIYARRUDHUMARRA-BUB

>https://www.blandshire.nsw.gov.au/Visitor-Information/Things-to-See-and-Do/Yindyamarra-Display

>https://www.visitlachlanshire.com.au/see-and-do/wiradjuri-culture/

>https://alc.org.au/our-history/

>https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/over-100-colonial-era-massacres-added-to-ongoing-project/qr2wi3ezc

>https://www.kidsnews.com.au/gold-rush/the-gold-rush-brought-people-from-all-over-the-world-to-live-together-in-one-big-multicultural-melting-pot/news-story/a1213fa5f5236d38e5ab44d619854715

(register of aboriginal reserves) >https://search.records.nsw.gov.au/primo-explore/search?query=any,contains,register%20of%20aboriginal%20reserves&tab=defaulttab&vid=61SRA&offset=0

>https://indigenous-histories.com/warangesda/

>https://archive.org/details/olddaysoldwaysbo0000gilm/page/6/mode/2up

>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiradjuri

>https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AboriginalProtection_Board

>https://www.parkes.nsw.gov.au/Community/Arts-and-culture/Wiradjuri-Ngurambang-Exhibition/Wiradjuri-language

>https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/138358977

Outback Pioneer, Sarah Musgrave

by Victoria Middleton

Sarah Musgrave nee White (4 May 1830-4 Oct 1937) was born on one of the nation’s first pastoral stations, ‘Burrangong’. She was Australia’s oldest, native-born white woman and, at the time of her death at age 107, was the oldest, living inhabitant.

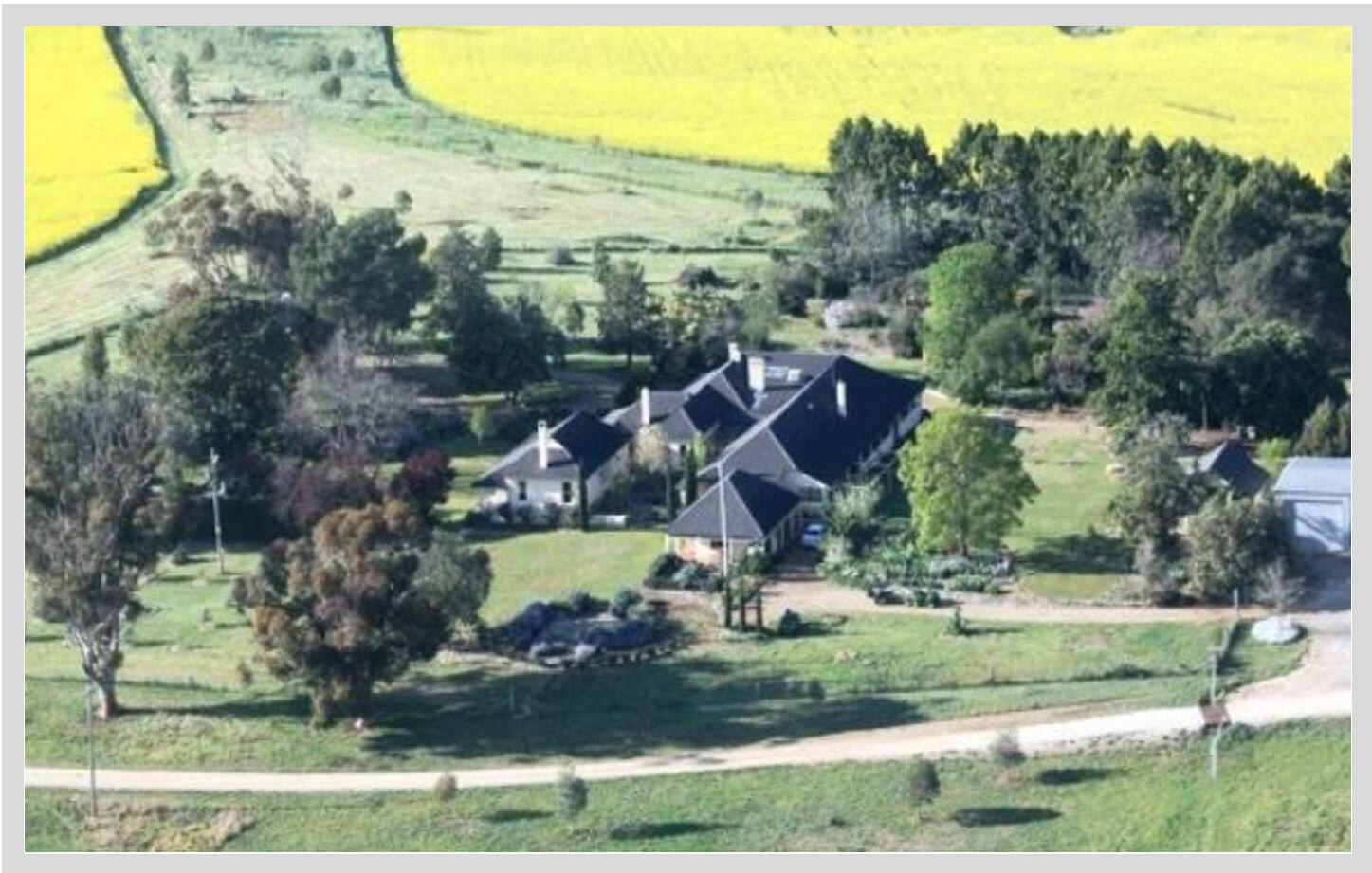

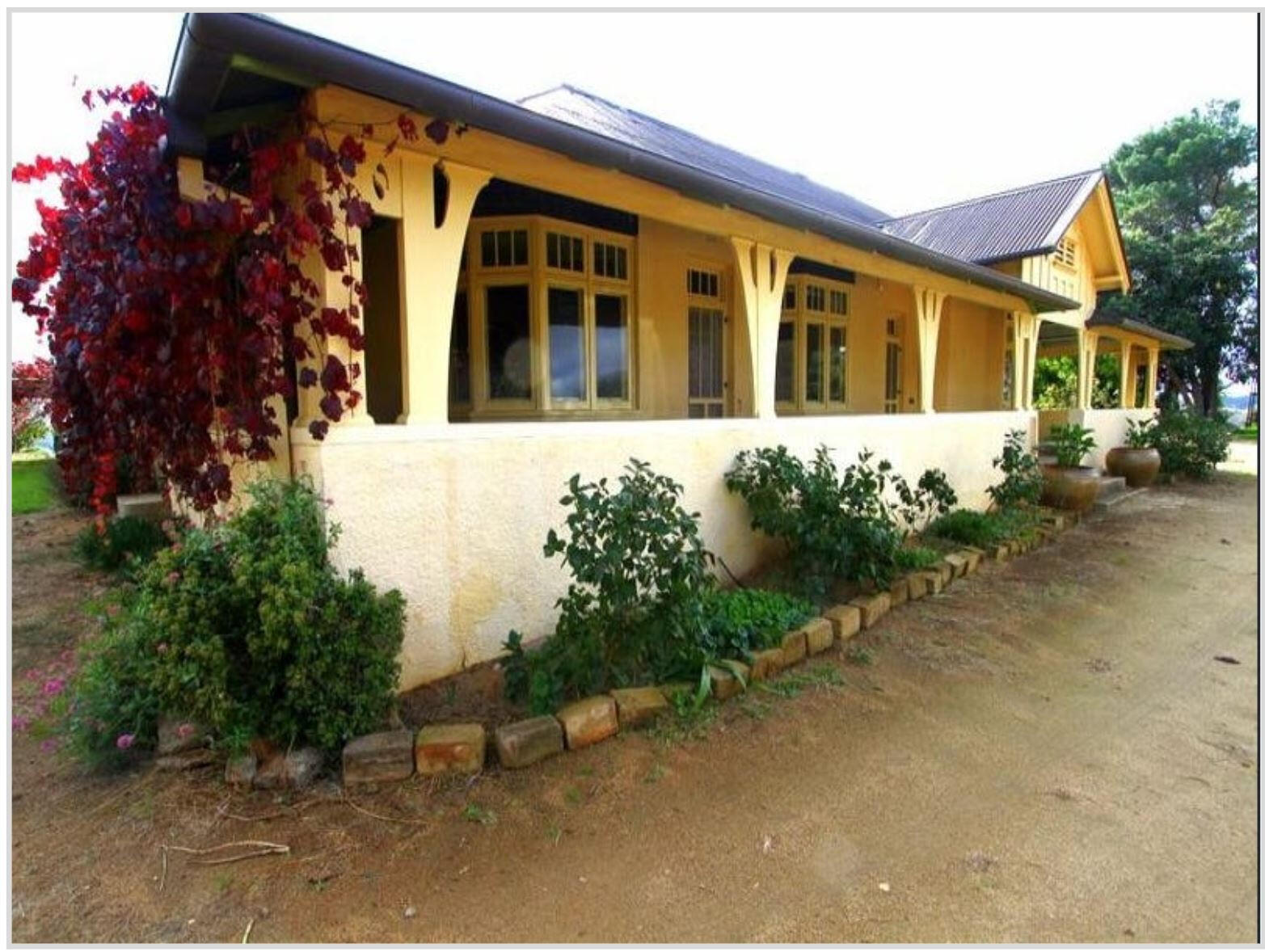

Burrangong Station lies west of Young and south-east of Barmedman in the Hilltops region. It is still a sheep and cropping enterprise today.

In 1812, brothers James and Thomas White came to Australia from Berkshire, England. Thomas and his wife went to Van Diemen's Land as horse dealers, and James took land on the Hawkesbury River.James White's farm and stock were decimated by a major flood which he escaped by riding a hay bale down the flood stream. James left his ruined farm and set up a prosperous butchery in George Street, Sydney, but the outback called and he paid the government ten pounds to squat on land in the central west.The chief of the local Lachlan tribe spotted White’s billy boiling and approached. The two men sat down to negotiate, before the chief granted James access to the land he called 'Burrownumditroy' in exchange for some of his provisions. As was popular at the time, White crowned the chief a king of his tribe, naming him ‘Cobborn Jackey’.

A ten-day corroboree followed with James White in attendance. Jackey advised him to build his home at Sandy Creek, so with saddle horse, pack-horse and the assistance of the Aborigines, James chopped a road through the bush and built Burrangong Station with dairy, homestead, quarters and outhouse, 260 miles from Sydney.This was officially the first station in the 'outback' of New South Wales.

In 1828, James White's brother, John (c1795- c1838) and his wife, Eliza (c1814-1889) travelled from England to join James at Burrangong.Unable to ride, John excelled as a gardener, planting vegetables, fruit trees and flowers. He brought the first feather mattresses to Australia. His wife was the first white woman in the district and the men had to teach her how to cook.Sarah White Regan Musgrave was born in their little house in 1830. For three years, they did not see another white woman.Thomas White was killed in a riding accident, and his widow and two children moved to Burrangong. Not long after this, Sarah's father, John died unexpectedly while walking through the bush to Murringo without water. Cobborn Jackey and James cut a straight road to Murringo through the bush to prevent it from happening to someone else.

In 1835, Sarah's mother gave birth in Gunning, only to return to Burrangong where bushrangers, 'Scotchie' Thompson and Thomas Whitton held them up. Their housekeeper, Mrs 'Terrible' Billy and her husband, 'Terrible' warned young Sarah, calling, "Croppy, come up!" Sarah ran to the house to tell her mother.The bushrangers - who lived in a cave in the Weddin Mountains, 20 miles away - were known to be ruthless. They gave the children bull's-eyes to stop them from crying while they ransacked the property. One of them found 200 natives hiding in the loft of a large house.The bushrangers got the workmen drunk before leaving and went on to kill two men at Currawong Station. They killed another two men in Goulburn after holding up twenty-two men.

In 1837, Sarah's mother married George Jones of Mulyan Station, Yass, and they moved to Victoria. Sarah stayed at Burrangong with her sister, and Uncle James became their guardian.

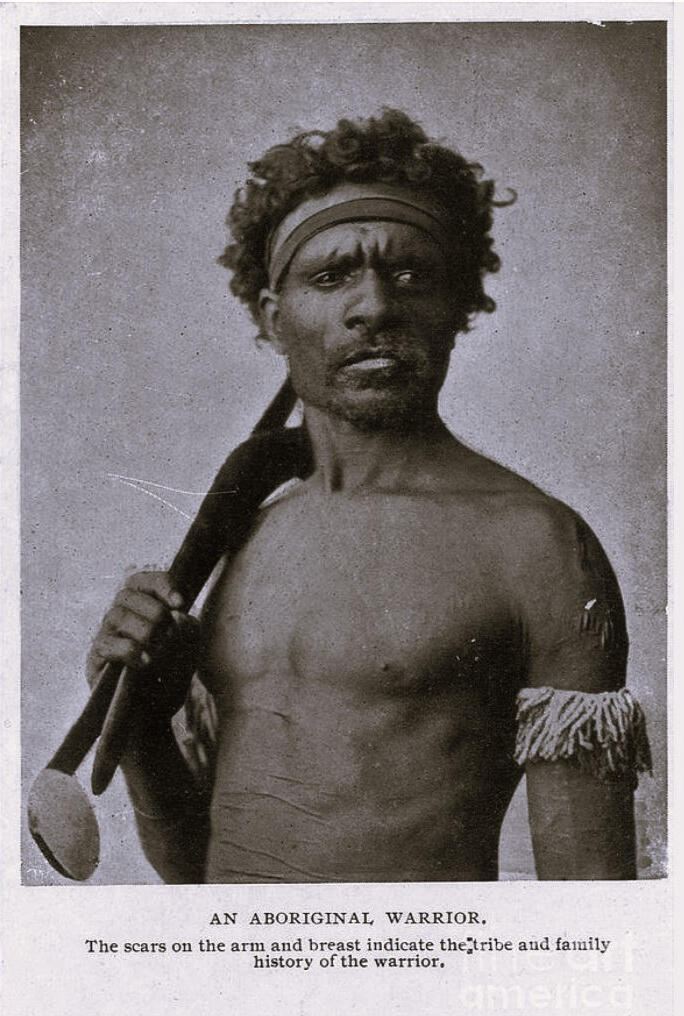

Sarah describes her earliest memories of the Aborigines (The Wayback, ch 4) as: "...fat and robust, and they were noted for the shapeliness of their legs and arms, but their degeneration followed rapidly upon the change from native habits. But they were always honest..."She called Cobborn Jackey "the Good Samaritan of his race, who lived for peace." He stepped in to protect the early settlers from some of his more spirited kinsmen who would never commit crimes if he was present.

The natives greatly feared firearms as much as they feared the 'debbil-debbil'. When 1000 Aborigines pitched their camp at Burrangong Station, they refused to hunt for food and demanded tea, sugar, tobacco, flour and meat to be provided indefinitely. Unable to provide provisions for such a large number, James White killed two of the natives' dogs, hoping to encourage them to leave. This act would come back to haunt him.To their horror, the natives scooped up the dead and living dogs, yelling, "debbil-debbil, come up!"

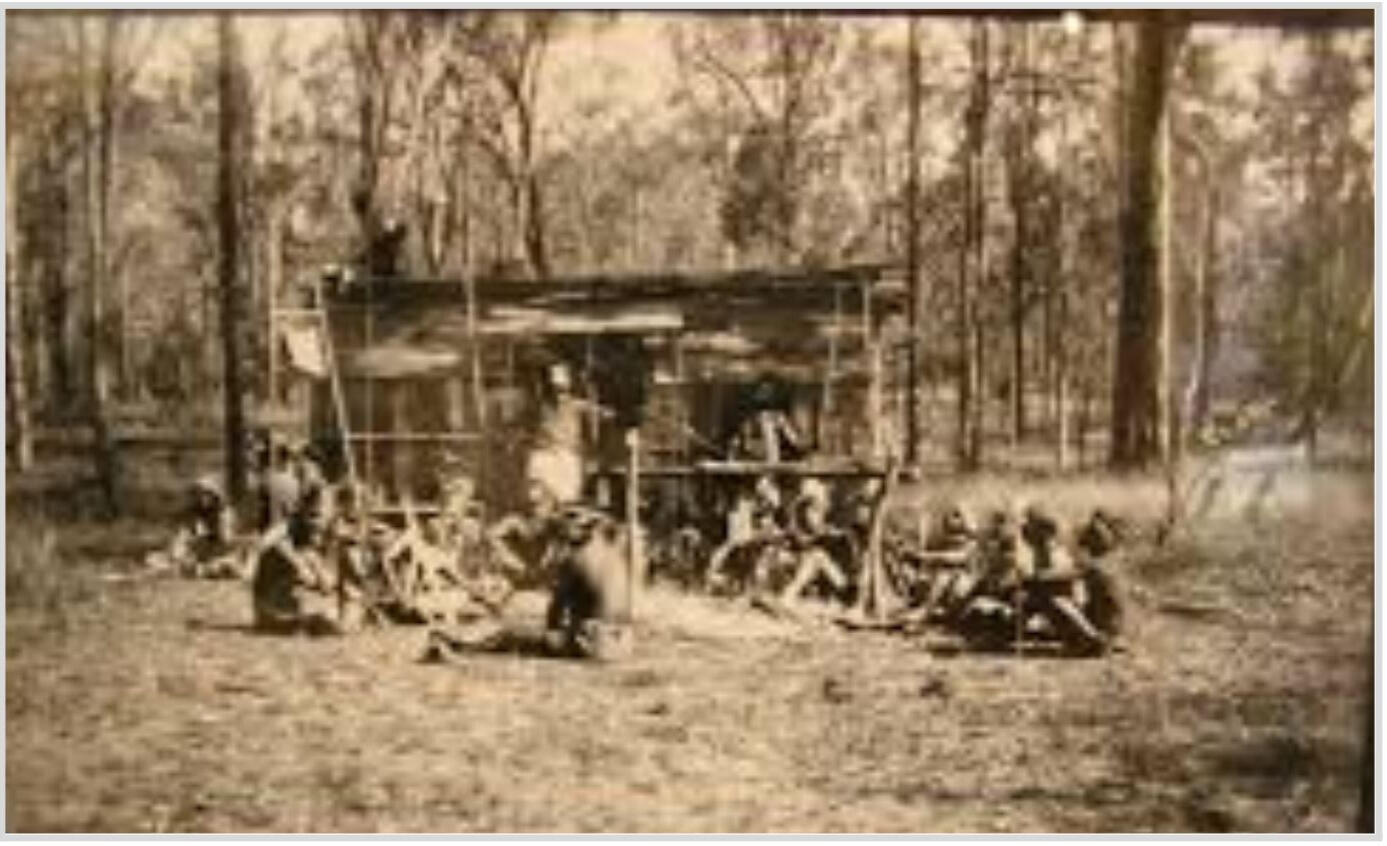

Sarah's uncle always returned from his yearly trips with gifts of knives, tomahawks, clay pipes, tobacco, chalk and red and yellow ochre for the natives. One day, the Wiradjuri - painted with lines of yellow and red, carrying spears, boomerang and waddy, and howling incessantly - descended the hill towards the station with Cobborn Jackey leading them. The men on the station grabbed their shotguns to shoot, but James White refused to fight them in the presence of King Jackey.Fifty yards from the homestead, the natives halted, sat down and broke into song. Jackey had united the Murrimbidgee and the Lachlan clans in peace, marching them 100 miles from the Snowy River to forgive Mr White for shooting the dogs belonging to the Murrumbidgee tribe.Jackey invited James White to a Corroborree as the guest of honour. A feast of wallaby, paddy melons, kangaroo rats and possums were cooked in a dugout of hot coals, and dancing and singing continured until four in the morning. An exhausted James White spent the next days listening to every man's apology.The Wiradjuri repaid White for his forgiveness by stripping hundreds of sheets of bark for roofing.

The Aborigines' strange burial practices were disconcerting to the settlers. Grief had to be demonstrated in screaming and body disfigurement, such as chopping tomahawks into their own heads and rubbing legs with burnt sticks. A child could not be buried without an adult male. The mother was forced to carry the dead infant until a tribesman died and, then, they would be buried together. They believed that the child would thus be protected in the grave.King Congo of Wallenbeen was buried with four babies after dying from illness when visiting Burrangong Station. Sarah recounts witnessing a 'miracle', when a medicine man squirted water on King Congo's face, before the king coughed and spat out a live lizard and a wood-adder before dying.

John Regan, the explorer who opened up the back country from Young, found the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee tribes' secret male initiation ground on land where the town of Wyalong now lies. The tribes believed the land had been desecrated and never conducted initiations there again.

On 1st January, 1850, locally produced stamps for letters were put into circulation in New South Wales. What you may not know is that the settlers had introduced a prepaid mail service ten years before, to expedite the delivery of mail outside of the city. Australia was the first country to introduce a prepaid mail service.

At this time, the Gold Rush was enticing workers to the discoveries on the fields and in the creeks. When the workers at Burrangong Station left to try their luck, the women jumped in to fill the void. The workers returned months later, poorer than when they left.James White was pleased to have them back. He was having issues trying to staff his other station, 'Spring Creek' and the seven sheep runs which had to be shepherded because of wild dogs.

In 1841, John Cartwright took land which now lies in Barmedman, calling his run, New Station. He placed William Wass there as manager.

Barmedman Station Homestead. Courtesy: Shirley Clay

From 1849 to 1852, the severest drought in The Bland in living memory crushed the hopes of local settlers, their farms and livestock. The water supply for man and stock lasted 12 months. When the creeks dried up, the settlers began to leave their holdings, because underground springs like the Curraburrama spring near Barmedman had not yet been discovered.The Lachlan River was too far, and when stock trampled themselves for water in creeks turned to a puddle and died there, and when settlers drank the last drops from the tanks and "...birds died in thousands, and dropped like berries from withered trees..." everyone left. The last man was Abel Buck, of Bland Creek.Abel's creek was the last to dry up and he believed rain would soon come. He called at Curraburrama homestead for water to drink and then it rained.

Burrangong Station was lucky because the water didn't run out. Sarah's uncle dug wells in the creek and tapped into the springs.

Never one to shy away from controversy, in chapter one of her memoir, The Wayback (1926), Sarah wrote:

"The blacks are now in the remnant stage of existence, and unless the Government changes its present stupid policy of unsympathetic guardianship, this native race must soon completely die out."

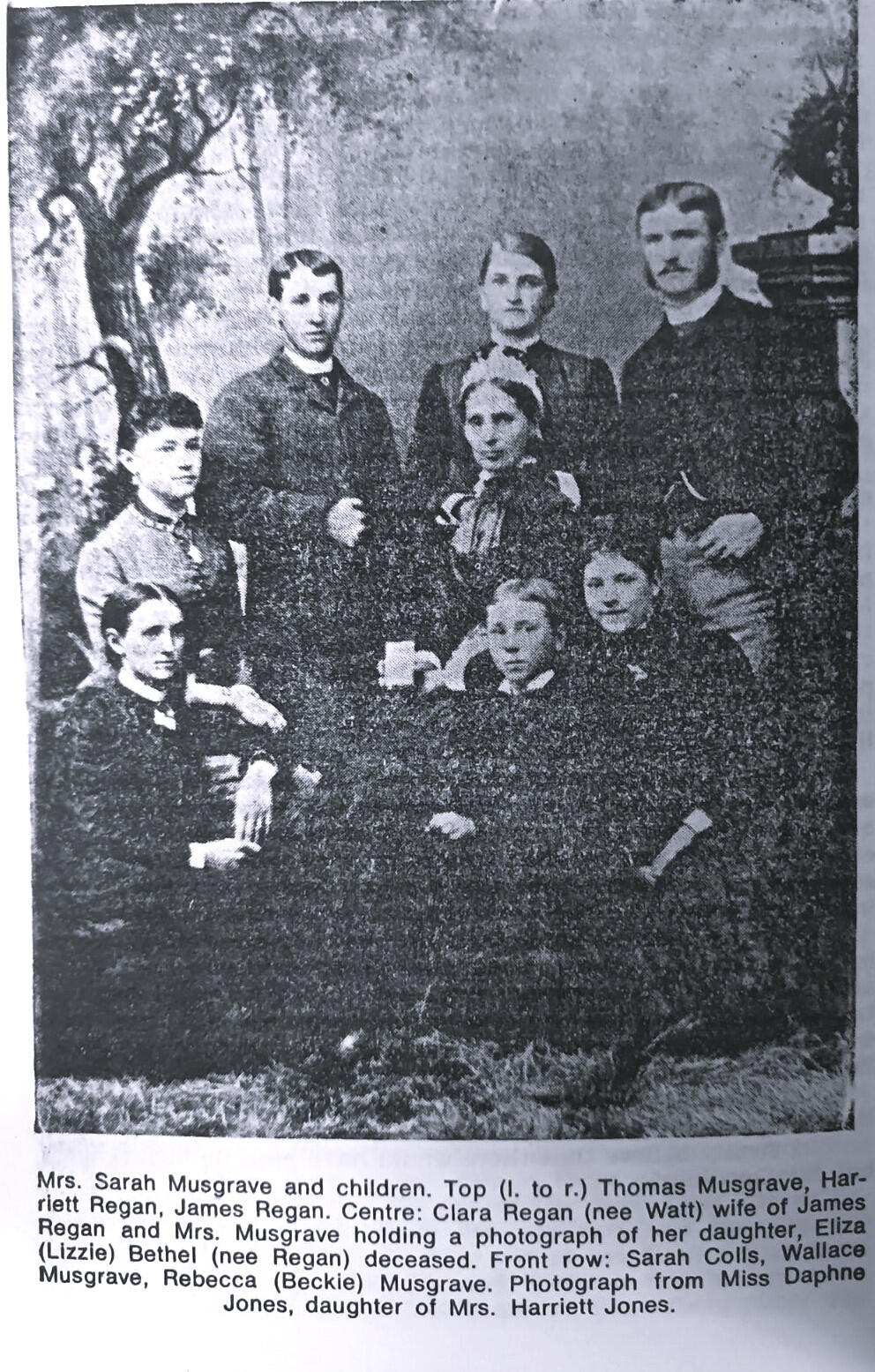

Sarah married Denis Regan (1833-1862) on July 1865. They rode 70 miles on horseback to the church in Yass. They lived at Burrangong Station and had four children: Sarah Alice Colls (1854-1890), Harriet May (1855-1933), Eliza Edith (1857-1890) and Denis James (1861-1941). Sarah's husband, Denis died at 29 years after succumbing to injuries from an accident he had while rounding up brumbies.

Sarah married Thomas Musgrave in 1865, at the age of 35, and they had three children: Wallace William (1871-1951), Rebecca Ann (1869-1908) and Thomas John George (1866-1910). They lived in Musgrave House on the other side of the creek from Burrangong Station.

Sarah wrote her book, The Wayback, at the age of 96 years. She died in her sleep on 4th October, 1937, aged 107, in Auburn, NSW. She is buried at Rockwood Cemetery, Sydney.

Sources:

Musgrave, Sarah, 1926, The Waybackhttps://www.findagrave.com/memorial/158914441/sarah-musgravehttps://images.findagrave.com/photos/2020/35/158914441db1ecc2f-67ca-46bd-9499-2e86ab6a7a93.jpeghttps://www.realestate.com.au/sold/property-other-nsw-young-7318958https://www.facebook.com/100053556976362/posts/429969040887290/

Karen Schamberger, 9 July 2015, An Inconvenient Myth — The Lambing Flat Riots and the Birth of White Australia, Conference Paper delivered at “Foundational Histories,” Australian Historical Association Conference 6-10 July 2015, University of SydneyFoster, Meg, 2019, The ‘Other’ Bushrangers: Aboriginal, African American, Chinese and female bandits in Australian history and social memory, 1788-2019https://historyobjectsculture.wordpress.com/2021/01/05/coborn-jackeys-breastplate/https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-08/bushranger-holds-up-historic-nsw-town-from-the-grave/9848508https://www.aasd.com.au/artist/248-charlie-numbulmore/works-in-past-sales/https://www.quora.com/Why-do-Australian-aboriginals-look-so-different-than-all-other-races-or-ethnic-groupshttps://allthatsinteresting.com/aboriginal-australians-oldest-culturehttps://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/160498461https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PostagestampsandpostalhistoryofNewSouthWaleshttps://archive.org/details/jimmyofmurrumbar00oakl0/page/22/mode/2uphttps://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/-/media/OEH/Corporate-Site/Documents/Heritage/regional-histories-new-south-wales-9518.pdfhttps://www.google.com/search?q=when+were+stamps+introduced+in+nsw&rlz=1C1ONGRen-GBAU964AU964&oq=when+were+stamps+introduced+in+nsw&gslcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIICAEQABgWGB4yCAgCEAAYFhgeMg0IAxAAGIYDGIAEGIoFMg0IBBAAGIYDGIAEGIoFMg0IBRAAGIYDGIAEGIoFMgoIBhAAGIAEGKIE0gEJOTA5N2owajE1qAIIsAIB&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#vhid=GCrP0WTe2FNqdM&vssid=lhttps://www.facebook.com/photo.php? ibid=1318312708188240&id=1306682212684623&set=a.1306712952681549&locale=zh_CNhttps://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Regan-902https://australianroyalty.net.au/tree/purnellmccord.ged/family/F7977/Thomas-Musgrave-Sarah-Whitehttps://www.myheritage.com/research/record-1-268290351-1-510784/denis-regan-in-myheritage-family-trees

'The Wayback': Seeking The Truth

by Victoria Middleton

In 1976, decades after Sarah White Regan Musgrave passed in 1937, a family reunion sparked the curiosity of her great niece, Carol Hope. Carol discovered that Jane Hope, the daughter of former convict and settler, Abraham Hope and Mary Ann Cowell, had once married Charles White (of Young NSW).

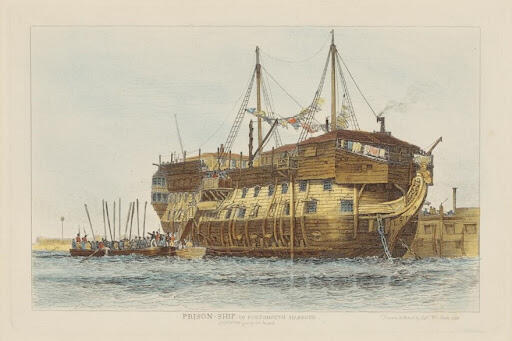

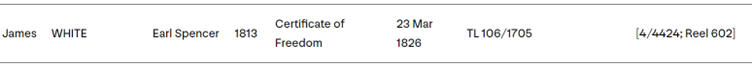

As mentioned in my article, ‘Outback Pioneer: Sarah Musgrave’, twice-married, Sarah White Regan Musgrave (4 May 1830-4 Oct 1937) was the first white person born in the Young District. While living in Auburn in 1926, she wrote ‘The Wayback’, a history of the Young District and its pioneers from c1830 to1880. [1]With my article almost completed, I came across the research of Carol Hope in ‘The Whites and The History of Young’, 1991, on a PDF titled: ‘Hangans At War 1’ by David Noakes, 2010. [2] This appendix includes Sarah Musgrave’s family who were featured in my article. What I didn't know was that Ms Hope's genealogical research had uncovered evidence of the convict origins of some of Sarah’s immediate family members.While searching for a Hope/White (Young) connection, Ms Hope discovered that Thomas White (who settled in Tasmania) had arrived in NSW on 11th June, 1813, with a life sentence and was convicted at Berks (Berkshire) Assizes as a native of Hants (Hampshire). The records showed a James White who arrived on the ‘Earl Spencer‘, on the 9th October, 1813, was convicted at Hereford and a native of Berkshire with a 14 year sentence. The 1814 Convict Muster revealed that James White was assigned to a James Singleton who resided at Windsor. In the 1822 Muster, James was a Ticket of Leave holder and also a landholder at Windsor. Sarah Musgrave mentions James White as having a ‘free grant‘ on the Hawkesbury River. [3]Convict shipping records show that Thomas White was shipped from Van Diemen‘s Land (as Tasmania was then known) to NSW on the ‘Kangaroo‘, in 1816, as one of the 40 male and 60 female convicts.

At this juncture, emphasis must be made to Sarah’s own account of her family’s ‘history’:

“In 1812, James White, his brother- Thomas -and wife, a friend named McKenzie and another man, sailed from England to Sydney. Thomas White, with his wife, went to Van Diemen's Land as a horse dealer, but the three others took up land under a free grant on the Hawkesbury River, where they started farming. White’s two partners grew tired of their pioneer undertaking and White bought them out.” [4]From the very first page of her book, Sarah omits the facts about her father, mother and uncles' convict pasts, and instead paints them only as free settlers and pioneers. To quote Ms Hope:

“It would appear that either Sarah Musgrave knew the truth and wrote a plausible story for future generations, or that her mother or Uncle James told the family history as they would have liked it known in the White families.” [5]Sarah wrote of her uncle, James White: “...he followed close on Surveyor-General Mitchell’s tracks…” when he set out to find a station in the outback in 1826, but this could not have happened. Major Thomas Mitchell arrived in Australia in 1827 and undertook his first expedition in 1831. James White received his certificate of freedom in 1826, but was still living in Sydney in 1828, (1828 Census).

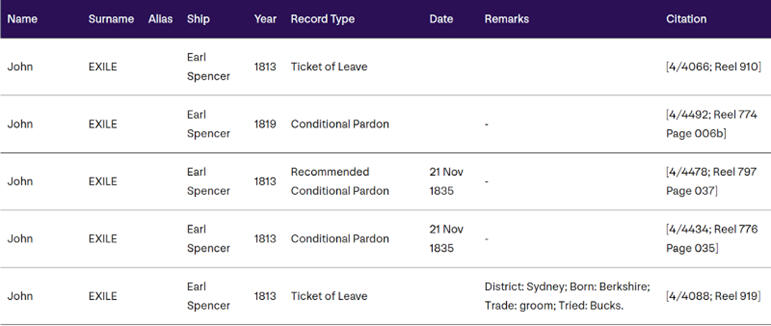

Marriage Indexes showed Eliza Waterworth had married John Exile in 1828. Church records for 1833, show John Exile, aged 35, as a Ticket of Leave convict on the ‘Earl Spencer‘ in 1813, coming free.

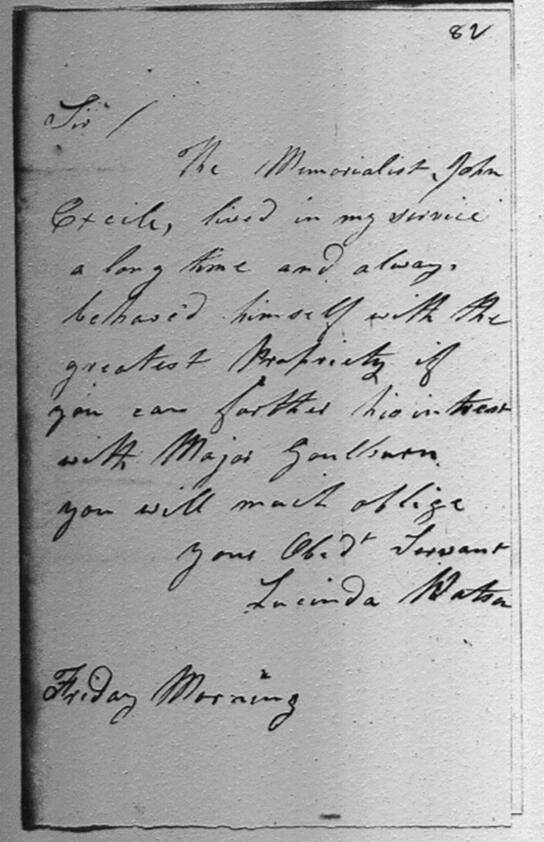

Researcher, Pam Cross, discovered proof that John White was using the alias of 'John Exile'. On 7th February, 1825, John Exile wrote a letter to the Colonial Secretary:

“The attention of your honour to the memoralist (i.e. John Exile) which I humbly ask permission to go to my brother, Thomas White, an opulent farmer called the Black Brush next unto Hobart Town, Van Diemen‘s Land. Memorialist now enjoys a Ticket of Leave five years - she came to this colony — ship ‘Earl Spencer‘ —the year 1813—and now having permission for a passage in the ship ‘Governor Macquarie‘ — which vessel sails on Sunday next…” [6]

A check of the county criminal registers showed the three Whites convicted for horse stealing and given a death sentence. Thomas and John (Exile) had their sentences commuted to life and James to 14 years.On 15th July, 1815, John Exile was reported as an absconded servant. On 10th May 1816, he arrived back in Australia from India on the ‘Hayeston’ under the assumed name of George Cavannagh. [7]

The Sydney Gazette (20 Dec 1817) reported John Exile as a runaway again. However, in 1821, while living at Windsor, he received a Ticket of Leave. He visited his brother, Thomas White in 1828 and the census of that year showed him as a servant to Gee Kaine, Butcher of Sydney.He applied for his conditional pardon but this was not granted until 30th June, 1835. [8]

The Australian newspaper in 1838, notes James White securing a grazing licence in the Western District.

In 1842, James had acquired a Pastoral Licence in the Lachlan District.

Around this time, a Mr Willmington wrote a letter of complaint to Lord Stanley in England about the squatters controlling large areas of the colony. Mention was made of the 377,000 acres controlled by James White in the Lachlan District – a vast step up from his convict days. [9]

Sarah wrote on P8 of 'The Wayback',that her father set out to walk through the bush to Marengo [Murringo] because "...he was not able to ride." This seems unlikely because John Exile [White] was a stable boy convicted of horse stealing in England. [10]Another strange comment in same book, claims Sarah's mother Eliza married George Groves of Mulyan Station in 1837, on the very day her son, George was baptised. Killing two birds with one stone?Shortly after they married, George and wife, Eliza left her 2 small daughters- Eliza and Sarah -to be reared by unmarried uncle, James White, before leaving to live in Victoria. [11]The question is: Why? Why would a mother not take her young daughters with her? Sarah offers no reason and doesn't defend her mother. She probably never understood it herself.

Mrs Eliza White Groves & daughters, Eliza White Regan (Curraburrama) and Sarah White Regan Musgrave (Burrangong). [12]

I'll leave the last words to Sarah Musgrave:"I am inclined to live in the days that are past. Perhaps it is only natural because, the happiest of my recollections are of the long ago." [13]

Sources:

[1] The Wayback, Musgrave, Sarah, 1926, Google Books https://books.google.com.au/books/about/TheWayback.html?id=-akfAQAACAAJ&rediresc=y[2] ‘The Whites and The History of Young’, 1991,’‘Hangans At War 1’, Noakes, David, 5/11/2010 https://freepages.rootsweb.com/haniganfamilytree/family/hanigan%20book%20with%20pics%20pages%20family%20section%205%20Nov%202010%20new%20format%20no%20dates.pdf[3] [4] Musgrave, Sarah, 1926, The Wayback, P1[5] ‘The Whites and The History of Young’, 1991,’‘Hangans At War 1’, Noakes, David, 5/11/2010, P234 https://freepages.rootsweb.com/haniganfamilytree/family/hanigan%20book%20with%20pics%20pages%20family%20section%205%20Nov%202010%20new%20format%20no%20dates.pdf[6] Museum of History NSW, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1825, John Exile

https://mhnsw.au/indexes/colonial-secretary/colonial-secretarys-papers-1788-1825/?query=john+exile&page=1[7] [8] ‘The Whites and The History of Young’, 1991,’‘Hangans At War 1’, Noakes, David, 5/11/2010, P235 https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~haniganfamilytree/family/hanigan%20book%20with%20pics%20pages%20family%20section%205%20Nov%202010%20new%20format%20no%20dates.pdf[9] Governor’s Dispatches to and from England, Historical Records of Australia, Vol xxii, April 1842-1843, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924071977692&seq=12[10] Musgrave, Sarah, 1926, The Wayback, P8[11] Musgrave, Sarah, 1926, The Wayback, P12[12] Musgrave, Sarah, 1926, The Wayback, photo, P80[13] Musgrave, Sarah, 1926, The Wayback, P91